By Senior Journalist,Colbert Gwain

We grew up in our compound in Jinaku-Muteff village, Fundong Municipality, North West Region of Cameroon, knowing that our father, Bobe Jude Thadeus Fulai Biyong, was a very rich timber merchant. We had mistakenly assumed that his close friend, Bobe Faie, who lived in mainland Abuh, was just using our compound as a warehouse and abode for the numerous timber sawing engineers or sawyers who came to work for Bobe Faie and were lodged in our compound.

My inquisitiveness usually led me to follow the sawyers to the dense Muteff forests, where they would cut down timber and manually saw it into various plank sizes and shapes. With one person holding the head of the saw and another inside the hole holding the other end, they would rhythmically saw out the planks while singing “Sawyer yen nge-eh! kamanda yi ikuo,” which translates to “The sawyer spends time suffering while the carpenter spends time enjoying money.”

Back in the community, the sawyers’ song reflected the stark contrast between the sawyer’s and carpenter’s lives. The sawyers often looked wretched and miserable, while the carpenters seemed like a new generation of Muteff village elites.

Each time I visited Bobe Ayungha, the most popular carpenter in the community, I marveled at the way he chiseled various shapes and sizes of planks into different furniture pieces, ranging from tables, chairs, beds, cupboards, desks, doors, and mirror frames. I used to be puzzled by how he would take a one-by-twelve size plank, laboriously produced by the sawyers, and seemingly destroy it by chopping it into pieces. However, when I saw the final product, I was always amazed by the carpenter’s ingenuity.

Youths who grew up in Muteff during our time would be amazed to hear that someone like Charlie Ndi Chia, who studied woodwork and joinery at the famous Ombe College and landed a great job at Pamol Plantation Co. Ltd., would abandon such a lucrative profession as a woodsmith to become a wordsmith or a mere vendor of words. Most of those who became carpenters in Muteff went through apprenticeships in workshops. That’s exactly the kind of advice my uncle in Abuh, the late Bobe Diom Vincent, spent time giving me, urging me to learn carpentry in his workshop attached to the main house in the compound rather than going to school to become a journalist.

Just as I was usually disturbed by the brutality with which the carpenter, Bobe Ayungha, would chisel up the plank sizes the sawyers had labored to saw, office holders and authorities in Cameroon have never been comfortable with the manner in which Charlie Ndi Chia chiseled out his words ever since he abandoned carpentry for journalism. It would appear his transition from carpentry to journalism brought a unique perspective and skillset to his writing, one that has likely served him well in his career as a journalist.

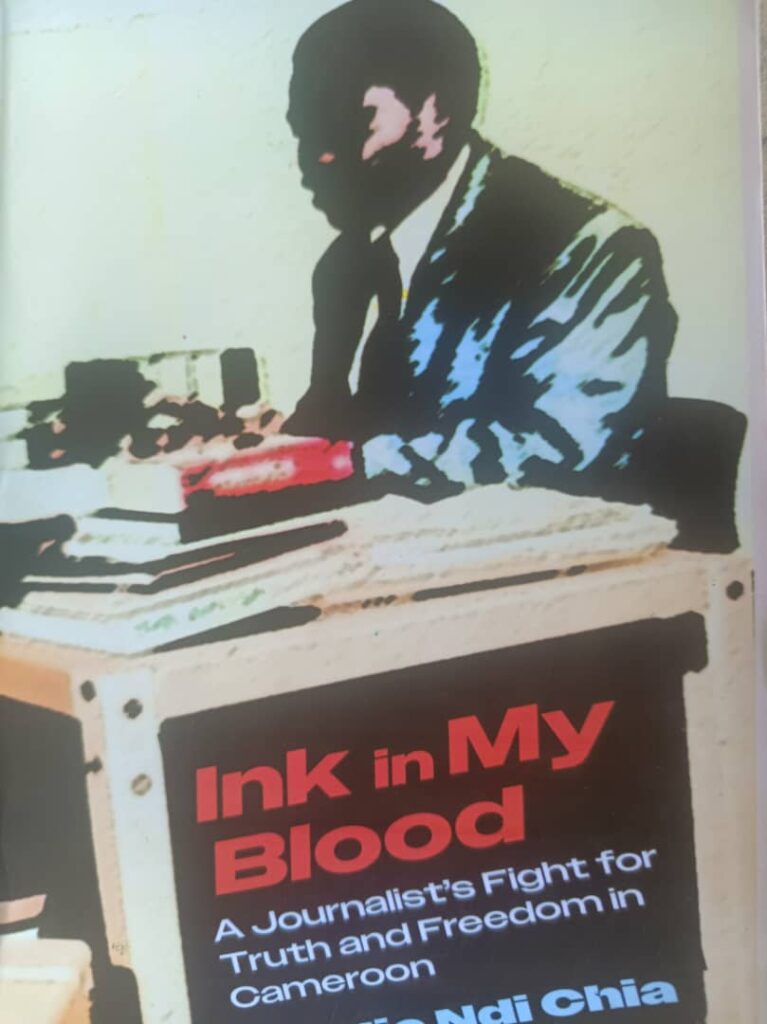

Charlie Ndi Chia’s memoir, “Ink in My Blood,” published by Langaa Research & Publishing Common Initiative Group (2025), chronicles the travails of a renowned Cameroonian journalist whose passion for journalism burned like a thousand fires. His worried mother’s scrutiny and his strict father’s insistence that he become a carpenter instead of a journalist never deterred him. As a young child who grew up as an adventurous boy, roasting sugarcane and playing pranks with falling trees, his only solace lay in “poking his nose into other people’s business.

The 122-page book, divided into 15 chapters plus an epilogue, covers Ndi Chia’s experiences from childhood, where he grew up with a curious mind, to imbibing the seeds of dissent as a teenager, finding his voice as a journalist, navigating the challenges of journalism by speaking truth to power, and facing legal and political trials. It also explores the price of truth, his experiences with the rise of independent media and multiparty politics, working at CRTV and navigating internal politics, his famous “Letter from the East” highlighting corruption and abandonment, the founding and running of an independent newspaper, his brutal departure from The Post newspaper, and his continuation of the fight at The Rambler newspaper, all set against the backdrop of a changing media landscape and the power of resilience.

For a man recruited as a carpenter at Pamol Plantations to turn around and become a whistleblower within the same corporation, and then show no remorse after being dismissed, speaks volumes about Charlie Ndi Chia’s character. The fact that he was arrested, tortured, and detained multiple times under the regimes of former President Ahmadou Ahidjo and President Paul Biya further attests to his unwavering commitment to truth and freedom in Cameroon.

This incident only fueled rumors across Cameroon that as an announcer at Cameroon Television, he would often usher in Prime News with the tongue-in-cheek phrase, “And now…lies from Studio 1 of CRTV.” Ndi Chia’s daring stunt on CRTV’s “Minute by Minute” TV program and, more notably, his “Letter from the East,” where he ended one edition with the memorable phrase, “I hate to say I hate the President,” remain unforgettable. He would also be remembered as the courageous Cameroonian journalist who boldly nicknamed himself “Amadou Ahidjo II” at a time when no one in government wanted to hear about the late President Ahmadou Ahidjo.

“Ink in My Blood” enriches not only the journalism world but also the literary world, thanks to its richness in stylistic devices. The title itself is a metaphor that compares Charlie Ndi Chia’s passion for journalism to blood flowing through his veins, highlighting his dedication and commitment. The memoir is rich in imagery, with vivid descriptions of his childhood, experiences as a carpenter, and time as a journalist that helps readers visualize his story and connect with his experiences.

A key literary device in this book is repetition, where Ndi Chia repeatedly emphasizes themes related to the importance of a free press, the challenges he faced, and the impact of his work. For example, Chapter 10, “Letter from the East,” and other chapters reinforce this theme, creating a sense of rhythm and emphasizing the significance of these issues.

Ndi Chia masterfully employs symbolism, with “ink” representing his profession and passion for journalism, and “blood” symbolizing the sacrifices he made, the challenges he faced, and his unwavering passion. Even in the face of danger, he remained resolute, as seen in his bold statement from the East.

The autobiographical narrative creates a sense of intimacy and immediacy, drawing readers into Ndi Chia’s world. The conversational tone, facilitated by the Q&A dialogue format with the “Grandchild,” provides insight into his thoughts and experiences, making the memoir feel personal and relatable. This format also sends a powerful message to journalists who fear speaking truth to power: that one can still speak truth to power and live to see their grandchildren as Charlie has done.

This memoir highlights the significance of a robust and free press in shaping society and promoting democracy, bringing to the forefront the challenges faced by African journalism, which starkly contrasts with Western journalism where such values are often taken for granted. While no journalist in Cameroon needed this book to recognize Charlie Ndi Chia as a towering figure in the fight for truth and justice, the memoir solidifies his place alongside renowned investigative journalists like Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. Their exposure of the Watergate scandal, which led to President Richard Nixon’s resignation, exemplifies the power of investigative journalism in holding those in power accountable.

If Charlie Ndi Chia’s work has not toppled presidents, it’s because of the nuanced African context we live in, where people were, as one famous musician put it, “nés avant la honte.” Nevertheless, his optimism in the epilogue is heartening—that a handful of dedicated journalists in Cameroon and Africa can still make a difference. This sentiment underscores the enduring importance of a free press in shaping the continent’s future.

A copy of the book is FCFA 5,000, the equivalent of about seven bottles of beer.